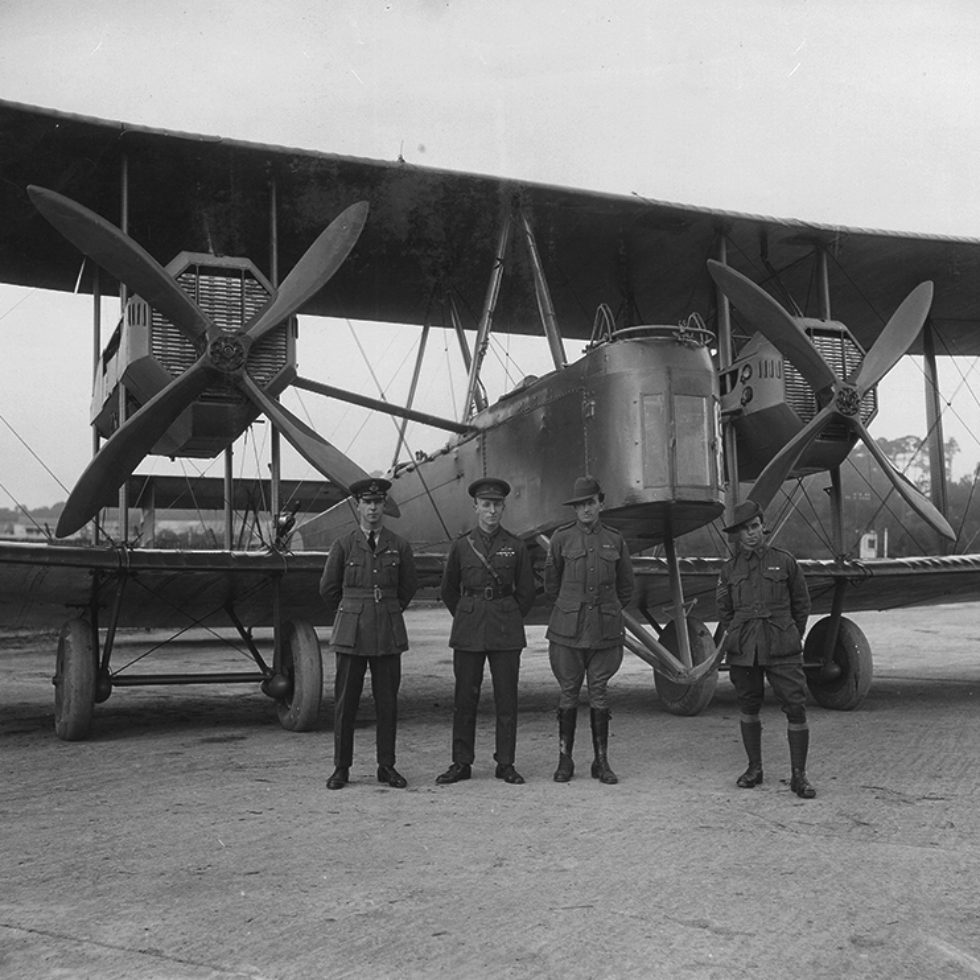

The Vickers Vimy was designed as a strategic bomber to attack German cities, but arrived too late to enter active service in WWI. With a 68ft (22m) wingspan, the huge biplane had a fuselage that looked like a long, thin cigar. At first sight, mechanic Wally Shiers noted to his fellow mechanic Jim Bennett: “My God Benny, fancy trying to fly this to Australia … she’d never last half the journey.” The crew also joked that the Vimy’s registration letters G-EAOU stood for “God ’Elp All Of Us”.

Powered by twin 360-horsepower Rolls-Royce Eagle Mark VIII engines, the Vimy was largely made of spruce pine covered by Irish linen. Twenty-five women workers were in charge of the fabric covering, sewing huge sleeves for the wings which were then stitched together with 10,000 knots. Water was used to shrink the fabric over the wooden skeleton before the plane was covered in multiple layers of dope – a kind of lacquer that was so toxic the women were ordered to drink lemonade to stop them from fainting.

Despite the crew’s trepidation, the Vimy proved her worth, guiding the crew safely home in 27 days and 20 hours. Ross Smith wrote of his admiration for the aircraft in his book 14,000 Miles Through The Air: “Not once, from the time we took our departure from Hounslow, had she ever been under shelter. And now, as I looked over her, aglow with pride, the Vimy loomed up as the zenith of man’s inventive and constructional genius.”

The Vimy caused major delays to Ross Smith’s victory lap of Australia, with the crew almost coming to grief when a propeller split two days out of Darwin, and fire engulfing the port engine in Charleville, Qld, a couple of weeks later. After a seven-week repair job, the Vimy limped her way south to Sydney, Melbourne and, finally, to the Smith brothers’ home town of Adelaide on 23 March 1920. On 5 April, the aircraft made its final flight from Adelaide to Pt Cook in Melbourne. As Ross Smith told a Daily Herald journalist on the day: “In a way I am very sorry to be leaving the Vimy, for during the past few months I have grown attached to it. Today I feel that I am leaving an old and trusty friend that has borne me many thousands of miles.”

You’ll find lots more on the England to Australia flight, and the Vimy’s engine troubles on the Australian leg of the journey, in our timeline. You’ll also find a list of 120 newspaper articles relating to the Vimy in 1920 on Trove.

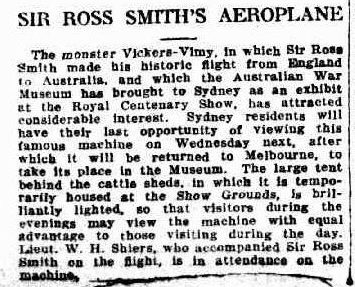

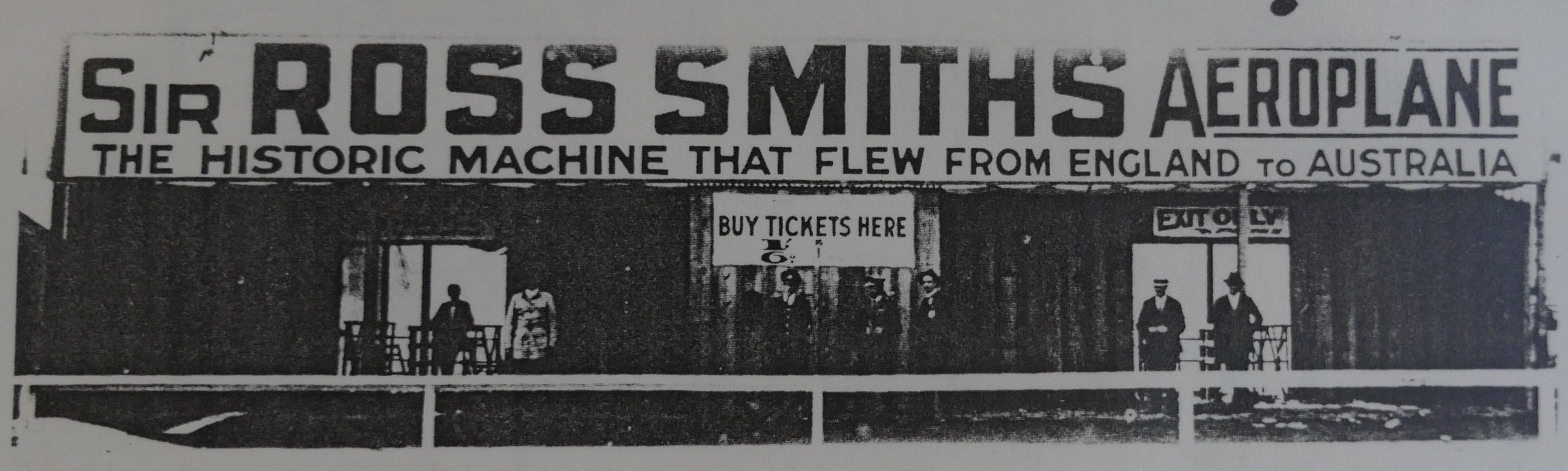

The Vickers Vimy was never flown again, but for the next two years the aircraft was regularly out of the hangar and put on show to raise money for the planned Australian War Museum.

Sydney Daily Telegraph article of the “monster” Vickers Vimy on show at Sydney’s Royal Centenary Show with mechanic Wally Shiers in April 1922. Tragically, Ross Smith and Jim Bennett died in England this same weekend. Source: Trove

The Vickers Vimy exhibition, possibly in Sydney. Unidentified newspaper clipping from the collection of the late Adelaide Vimy enthusiast Arthur Robertson.

When the Australian War Museum opened in the Melbourne Exhibition Building in the second half of 1922, the Vimy became a star exhibit. You can see it in the background of the image below.

Black and white image of aircraft, bombs, paintings, and photographs displayed in the Australian War Museum, Melbourne Exhibition Building, around 1922, including the … Vickers Vimy. Photo courtesy Museums Victoria.

The Australian War Museum took up temporary residence in Sydney’s Exhibition Building in 1925, and the Vimy was again on display. Below on the left you can also see the single-engine DH9 flown from England to Australia by Ray Parer in the Great Air Race.

Photo courtesy Australian War Memorial [J02197]

When the Australian War Memorial was officially opened in Canberra on 11 November 1941, the Vimy again took centre stage, displayed alongside WWI German bombers and Ray Parer’s DH9.

The Canberra Times’ coverage of the opening of the Australian War Memorial in 1941. Source: Trove

On 1 July 1955, Sir Keith Smith wrote to then Prime Minister Robert Menzies to raise his concerns about the fate of the Vickers Vimy, after learning the aircraft had been removed from the Australian War Memorial.

“I venture the suggestion that in the years to come the aircraft will be of increasing historical interest to Australians and visitors alike … I suppose it is too late for anything to be done now, but I felt that I should personally let you know how concerned I am about the matter.”

Prime Minister Menzies was swift to respond, replying on 12 July that “the removal of the machine from the War Memorial building does not carry any imputation that it has suffered, or is likely to suffer, any diminution of its historical value”.

When the machine was first placed in the War Memorial none of us could have foreseen that Australia would be forced to fight in another major war and that we would be required to find room in the building for a great number of exhibits perpetuating our further efforts on the field of battle. That position, however, did arise and the War Museum has had to be re-organised … At this juncture, certain people in Adelaide, a city that has always been proud of being your birthplace, asked if they might have the machine on exhibition in the city.

To view a PDF of both letters, copies of which are held in South Australian Aviation Museum library, please click here.

In 1956, the Royal Aero Club of South Australia and South Australian Senator Keith Laught (among others) established the Sir Ross and Sir Keith Smith War Memorial Committee and launched a public appeal to raise £30,000 to house the Vimy in Adelaide. Donations poured in from all parts of Australia and overseas including England and New Zealand. The Vickers Corporation chipped in £5000.

The high-powered committee secured South Australian Governor Sir Robert George as Vice-Regal Patron and Qantas co-founder Sir Hudson Fysh as one of nine vice-presidents. To view a PDF of a 1958 letter signed by the chairman and showing a full breakdown of the committee, please click here.

Significantly, the South Australian Government insisted that the Federal Government maintain ownership of the aircraft. The Federal Government also provided a prime location outside the original terminal at Adelaide Airport.

At 11.40am on 3 November 1957, disaster struck while the Vickers Vimy was en route to its new home in Adelaide. Fire engulfed one of two RAAF lorries transporting the aircraft, with responding country fire crews pouring water onto the wreckage for three hours. Luckily, the fuselage was undamaged. In an article headed “FAMOUS OLD PLANE AFIRE”, The Advertiser reported:

The mainplane and other parts of Sir Ross Smith’s famous Vickers Vimy aircraft were destroyed near Keith yesterday when fire broke out among crates on one of two RAAF semi-trailers which were bringing the parts to Adelaide. Other parts destroyed included propellers, engine cowlings and radiators. The cause of the fire, which started in the centre of the load, is not known. When the fire broke out the driver of the semi-trailer drove to the side of the road followed by the other vehicle.

Both The News and The Advertiser reported Keith fire officer Roger Gransden as saying the RAAF party had been “most secretive” about the blaze. “The men, particularly the warrant officer who appeared to be in charge, were very upset,” he said.

Within days the memorial building’s scheduled opening on 15 December was postponed, with Memorial Committee chairman Group Captain RM Rechner declaring: “Whatever has been destroyed will be replaced.” The Department of Defence Production, however, was directed to restore the Vimy to “mock-up conditions” only, so that “externally it appears sufficiently like the original to be accepted as such by persons other than those with special knowledge”.

Deane Leicester remembers his father Walter working on the Vimy’s upholstery and wing cladding at Parafield after it was partly destroyed in the fire. “Dad worked at the Department of Aircraft Production with another upholsterer by the name of Alec Gibb – they mostly did the DC-3s so the Vimy was something very different,” Deane says. “I helped him cover another plane once in Irish linen and dope [as Walter and Alec would have done on the Vimy’s outer wings which needed to be replaced] and it was terribly smelly and very volatile.”

On 9 November The Advertiser reported that an RAAF Court of Enquiry at Edinburgh Airfield had completed an investigation into the blaze, with statements also gathered from eyewitnesses in Keith. Rumours spread that a cigarette butt might have sparked the blaze. If the cause was ever officially established, it doesn’t appear to have been made public.

Above you can see the undamaged fuselage, wing stubs and under-carriage of the Vickers Vimy in the unfinished memorial building at Adelaide Airport in 1957. Images copyright: News Corporation.

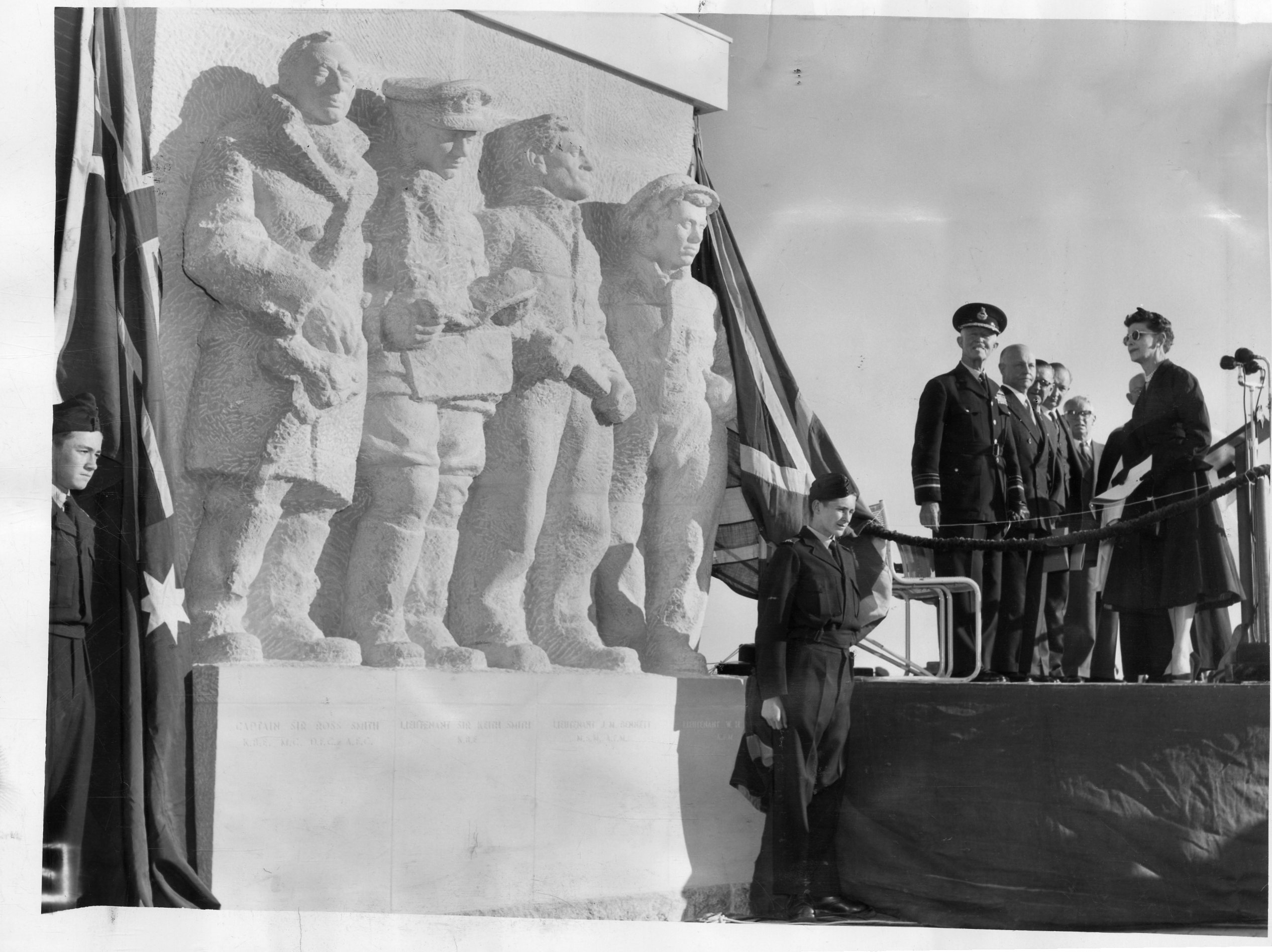

On 26 April 1958, 40,000 people flocked to Adelaide Airport to witness Air Marshall Sir Richard Williams officially open the Sir Ross and Sir Keith Smith Memorial and unveil the John Dowie sculpture of the four Vimy crew members. Sir Keith had died of cancer in December 1955 (only months after writing to Prime Minister Menzies about the Vimy) so Wally Shiers was the only surviving Vimy crew member at the opening. Sir Keith’s widow Lady Anita Smith was also a guest of honour.

Sir Richard, who had been Ross Smith’s commanding officer with No. 1 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps during WWI, described the aviator as a “most meticulous” pilot. “Had Ross not died so tragically in 1922 I have no doubt he would have made an even greater contribution to aviation,” he said.

The then Premier Sir Thomas Playford described the memorial as a “fitting commemoration of one of the greatest achievements of SA’s sons”. He continued:

It is fitting that the site chosen for the memorial is the centre of aerial activities of civil aviation in SA, where every person who today enjoys the great advantages of modern transport can stop for a moment and ponder on those who contributed to them.

The Advertiser, 26 April 1958

The unveiling of John Dowie’s sculpture of pioneer aviators Captain Sir Ross Smith, Lieutenant Sir Keith Smith, Lieutenant J M Bennett and Lieutenant W H Shiers at the Vickers Vimy memorial at Adelaide Airport. In the foreground on the dais are Air Marshal Sir Richard Williams, who unveiled the memorial and Lady Smith (Anita), widow of Sir Keith Smith. Behind them (from left) Lord Mayor of Adelaide (Mr. Lancelot (Lance) Morton Spiller Hargrave), the Minister for Defence (Sir Philip McBride), the Premier (Sir Thomas Playford) and the only surviving member of the crew, Mr W. H. (Wally) Shiers, 27 Apr 1958. Image copyright: News Corporation.

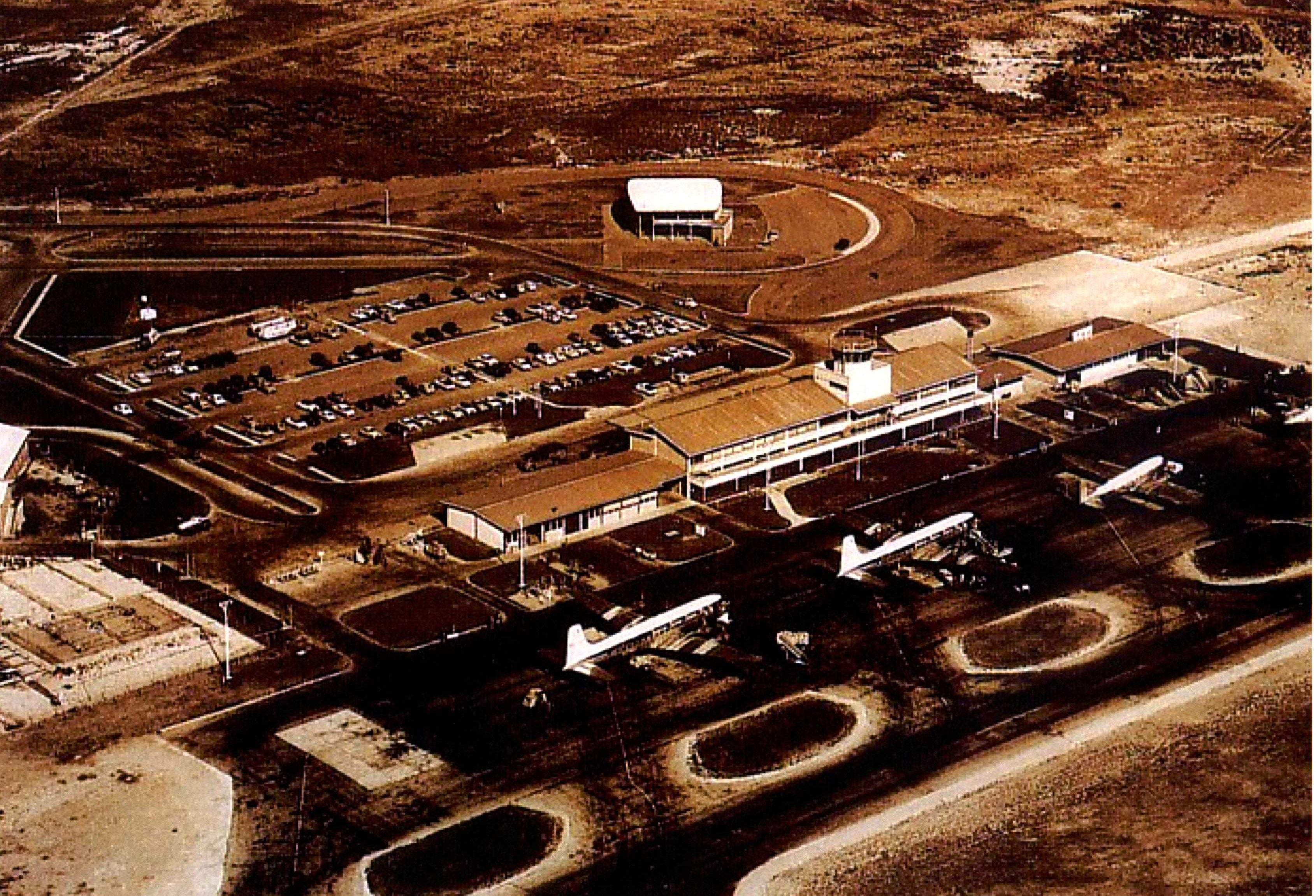

Aerial view of the memorial soon after opening. Photo courtesy of the West Torrens Historical Society.

In 1987, protective screens were erected around the Vimy building to protect the aircraft from ultraviolet light. This was largely the result of lobbying efforts by Norman Pointing, a maintenance engineer who’d helped to restore the Vimy in 1957 and carried out a further major restoration in the early 1980s when it became clear the Vimy was deteriorating under extremes of temperature and humidity. South Australian artist Stefan Twain-Wood was contracted to paint a Vimy mural on the screens surrounding the building. Sadly the screens were damaged in the sun, too, and eventually thrown away.

In May 1998 the Commonwealth privatised Adelaide Airport. Under the terms of the lease agreement, the new airport lessee, Adelaide Airport Limited, took responsibility for the management and operation of the Sir Ross and Sir Keith Smith Memorial, and for maintenance of the building and is contents.

With the opening of Adelaide Airport’s new state-of-the-art Terminal 1 in 2005, the Vickers Vimy no longer had pride of place outside the main terminal entrance. To link the Vimy with the new Terminal 1 building, Adelaide Airport and Arts SA collaborated to develop the Vimy Walk – marking each stopping point that the Vimy made on its epic route to Australia.

Ahead of Australia’s 2019 federal election it was announced that a new state-of-the-art facility would be built for the Vickers Vimy at Adelaide Airport.

Announcing a $2m funding commitment by the federal Morrison Government, SA Liberal Senator Simon Birmingham said it was a major win for South Australia’s cultural heritage, for tourism, and would serve to educate generations to come of our state’s pioneering and aviation history.

The $2m commitment (matched by the federal Labor opposition) was matched by the South Australian Marshall Government and Adelaide Airport Ltd, taking the combined total for the rehousing project to $6m. The Vimy is set to be moved to a prominent position within the new airport terminal in 2021.

Adelaide’s Sunday Mail, 11 May 2019

Only two original Vimy aircraft remain in the world – Alcock and Brown’s Vimy at the British Science Museum (where it was installed soon after the famous Atlantic crossing in June 1919) and the Smith crew’s Vimy at Adelaide Airport. Smithsonian Air and Space Museum curator Alex Spencer believes Ross Smith’s Vimy should be as iconic to Australia as Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St Louis is to the United States.

Written and researched by Lainie Anderson, author of Long Flight Home, which tells the story of the Great Air Race through the eyes of Vimy mechanic Wally Shiers. Further information on the Vimy’s move to Adelaide and maintenance and custodianship of the aircraft in subsequent years can be found in a comprehensive profile of Sir Ross Smith and the Vickers Vimy crew, written by Mike Milln at the South Australian Aviation Museum (head to page 16).