The weather report in Hounslow, England, was dire on the morning of 12 November 1919: “Totally unfit for all flying.” Ross Smith took off anyway, fearing worse weather with the oncoming European winter, and knowing his French rival Etienne Poulet was already well on the way to Australia.

The snowstorm they encountered that first day over France was so fierce he was forced to fly at 11,000 feet (3,350 metres) to escape towering cloud banks. Their goggles and cockpit dials froze. After six hours of flying blind, they spotted a hole in the clouds and flew down to earth, discovering they were just 40 miles from Keith’s predicted location of Lyon, France.

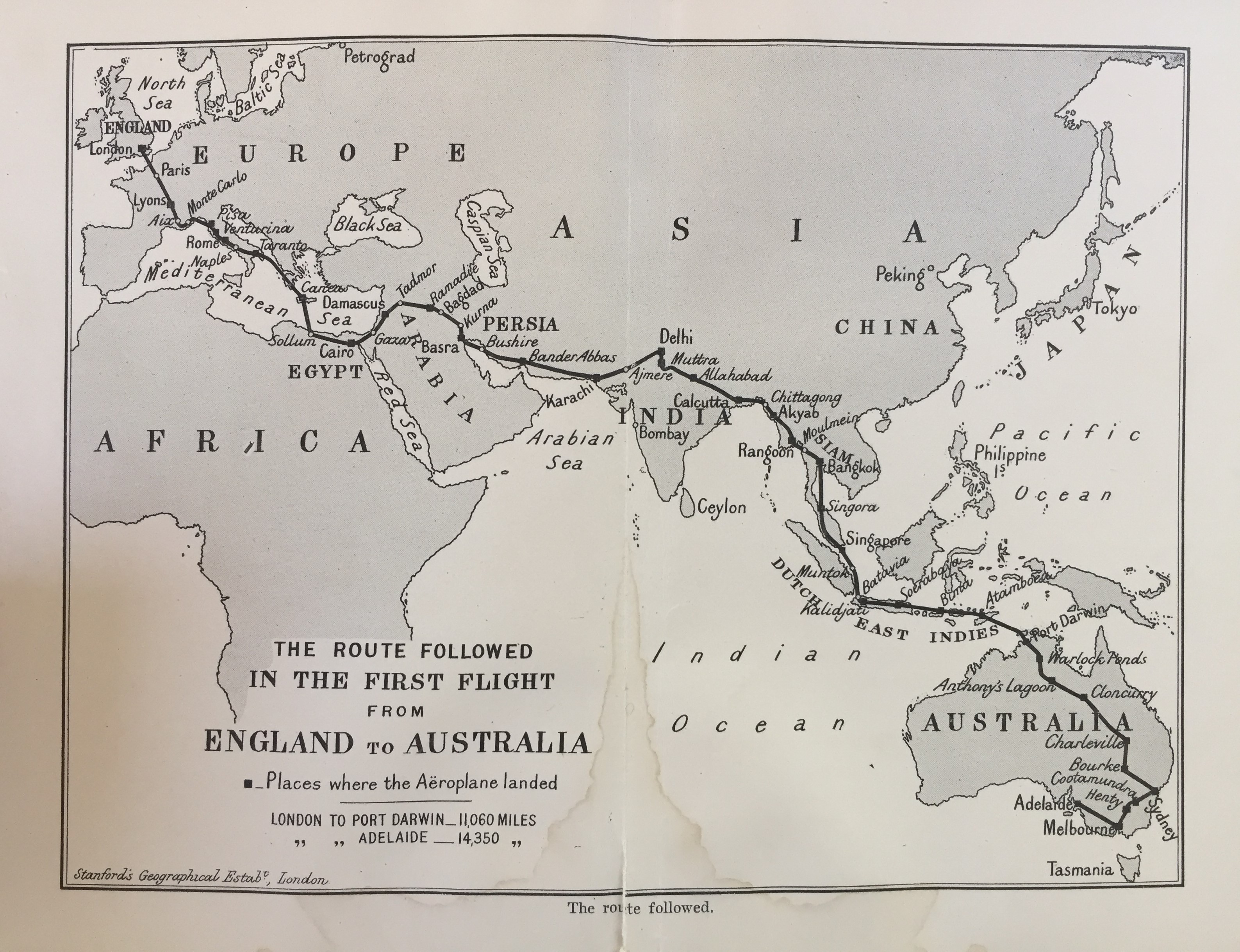

The epic flight route, published in Ross Smith’s personal account, 14,000 Miles Through The Air, MacMillan & Co 1922.

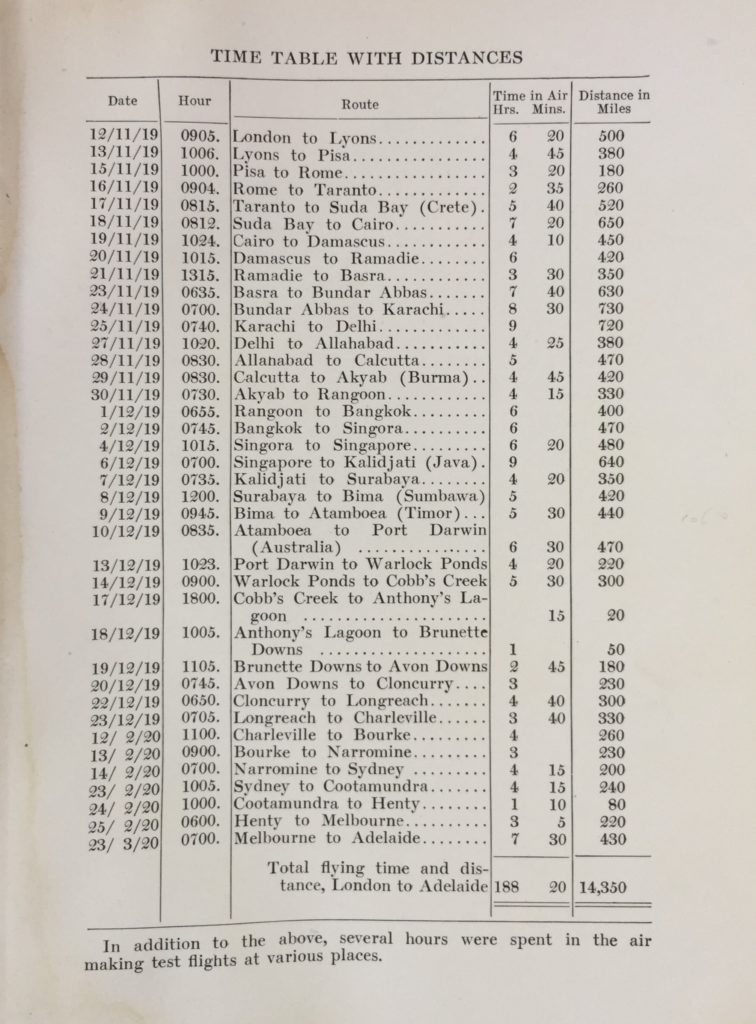

Ross Smith’s diary of dates, departure times, daily flight duration and distances, published in 14,000 Miles Through The Air (MacMillan & Co, 1922).

Over the following 28 days, they passed through the world’s climatic zones, and the weather threw everything at them: European snowstorms, desert sandstorms and tropical downpours that lashed the skin from their faces. But across the world – from Italy to Indonesia, Crete to Calcutta – people came to their aid.

In Pisa, overnight rain left the Vimy surrounded by a lake of water. Thirty Italian mechanics worked in vain to get the six-tonne plane free of the sludge. Ross Smith told Jim Bennett to run beside the fuselage, holding the Vimy’s tail down and her nose up out of the mud, until they became airborne. When the wheels left the ground, Jim sprinted for the back cockpit and Wally hauled him in.

In Ramadie, near Baghdad, 50 Indian cavalrymen stood sentry over the plane all night, using their weight to prevent her from busting up or being blown away in a raging desert sandstorm.

In Surabaya, Indonesia, villagers took the bamboo matting walls from their homes and “came streaming in from every direction” to lay a 300m runway over soft mud that had threatened to entrap the Vimy. The crew called it Matting Road.

No-one knew the route quite like the Smith brothers. Having served with the Royal Flying Corps in Britain, Keith was experienced at flying in freezing temperatures, while Ross knew the deserts of the Middle East like the back of his hand. Directly after the war Ross had flown from Cairo to Calcutta before scouting possible landing sites by sea all the way down to East Timor.

That knowledge – as well as the contacts Ross made – proved one of the keys to the crew’s success.